Multicellular development is weird

It’s not how we build things.

Human construction is top-down. We begin with prefabricated parts, a plan, and someone to carry it out. Think IKEA: a flat pack of parts, a fold-out manual, and a brave soul with an Allen key.

But development doesn’t appear to follow a plan. There are no obvious instructions, no prefabricated parts, no visible assembler. The system just builds itself from the bottom up.

Consider what it accomplishes

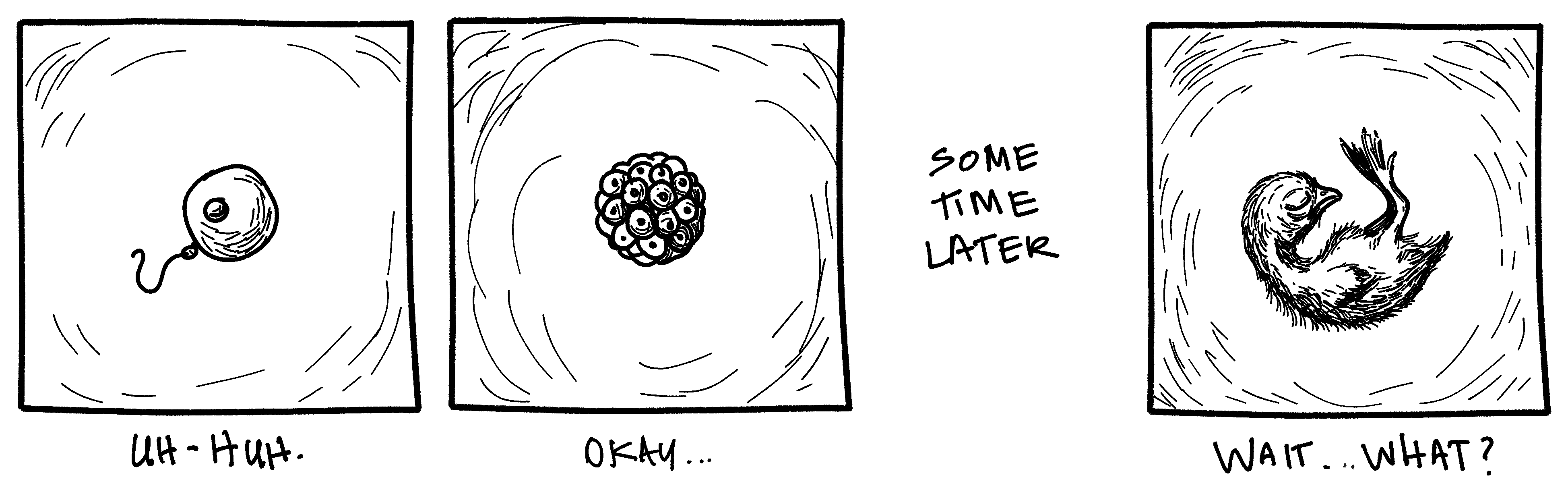

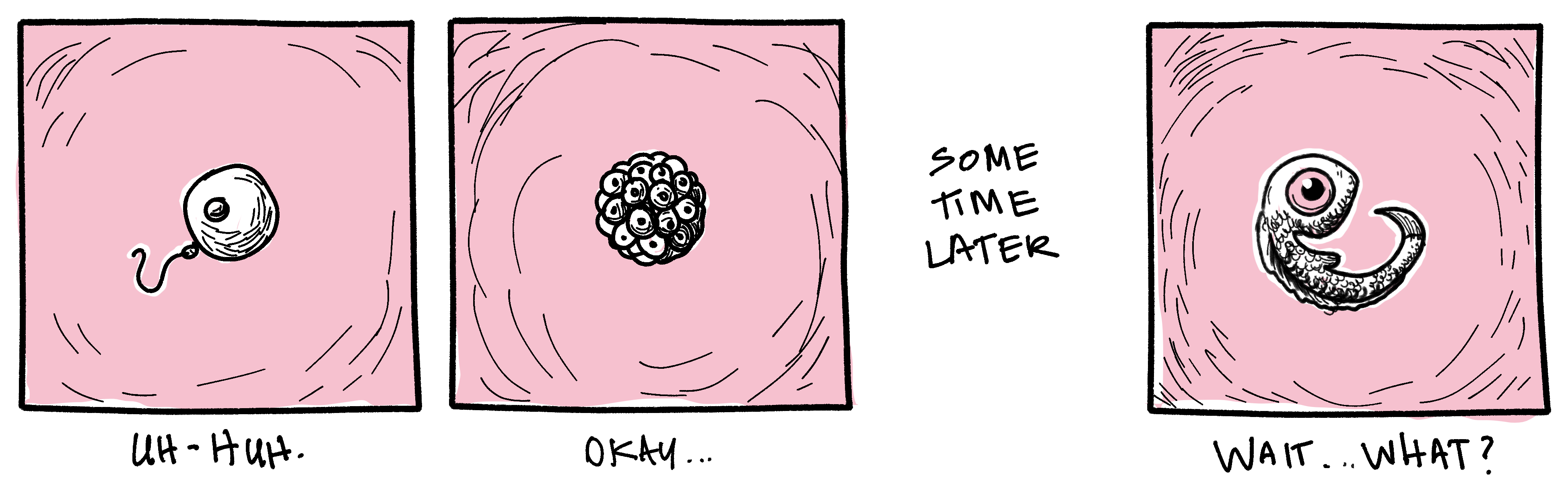

From a single cell and a suitable environment, a complex organism emerges — with limbs, organs, and attitude. How does such order unfold from one tiny cell?

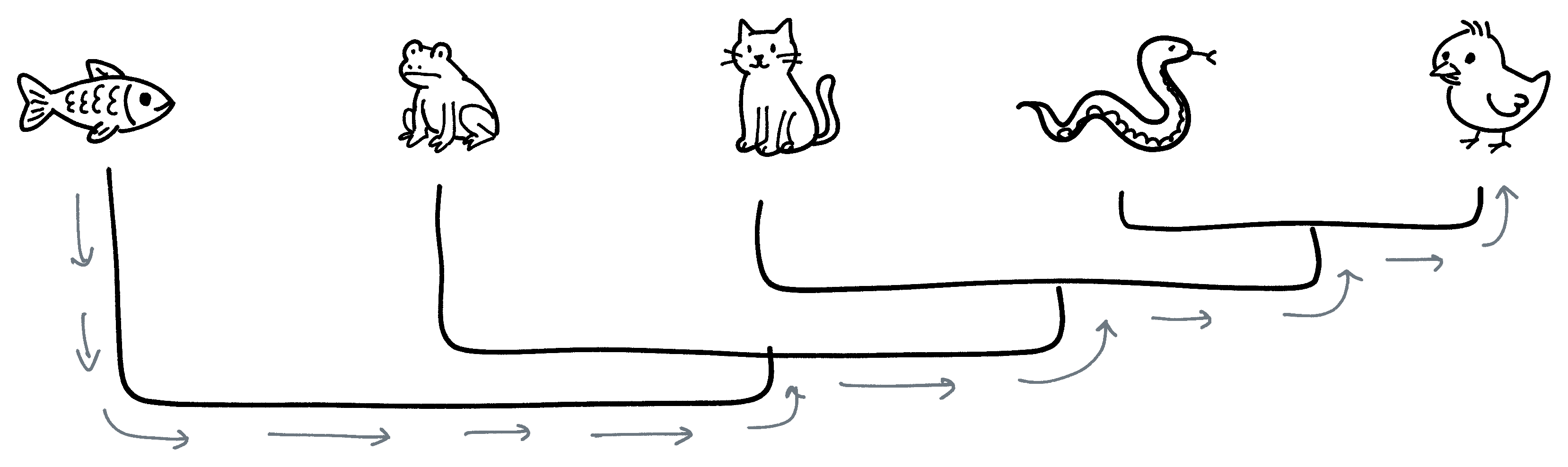

The process producing this order is finely controlled. Start with a different cell and you get a different, species-typical arrangement of parts — fins, not wings; scales, not feathers. How is it precisely guided to such specific outcomes?

The process is also incredibly malleable. A chick and a fish are very different. Yet they are connected by a continuous series of small, viable changes. How can such a process be gradually modified?

This is truly marvelous…

But to an engineer, it is also very perplexing.

Everything yells for a plan: something stored in the cell that explains form, something instructive that precisely guides the process, and something that can be modified to produce these wildly different outcomes.

The obvious answer is DNA, but that looks nothing like a set of instructions. Maybe it all just comes together in a magnificent feat of self-organisation. But how would that work?

So we have a puzzle. But we could treat it as a design problem. How could you build something that works like this? Not a complete reproduction, but something minimal that captures the essence of the problem.